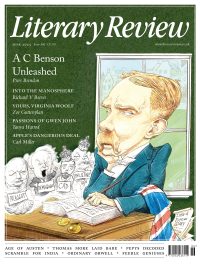

Carl Miller

Return of the Mac

Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company

By Patrick McGee

Scribner 438pp £25

It was 1997 and Apple was kicking off a campaign to rebrand itself with a new television advert. ‘Here’s to the crazy ones … The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently,’ ran the voiceover. Patrick McGee’s book opens in this era, with Apple locked in a death spiral. It is on the brink, barely able to pay its staff, having to sell its factory in order to survive. To save itself, Apple needs a radical new vision. So far, so conventional. We all know the rest of the story – or at least we think we do: Steve Jobs tears up the rulebook, reimagines the computer and everything changes forever. ‘Think different,’ Jobs exhorted in that campaign.

Only the star of McGee’s book isn’t Jobs. Nor is it Apple’s design chief Jony Ive. The protagonist is Tim Cook, who became Apple CEO in 2011. ‘Here’s to the sensible ones … the round pegs in the round holes,’ joked Bloomberg Businessweek when it ran a profile of him. Far from being a renegade, Cook once spent thirteen hours with his management team going through hundreds of pages of Excel spreadsheets related to supply and demand around the world. By inspecting spreadsheets, Cook ‘could make grown men and women cry. A few screamed at him, leaving the room, never to come back,’ writes McGee.

But Cook did think differently, just in another way from Jobs. Apple in China is about a vision had by Cook and his subordinates that, McGee argues, was no less radical or profound than any of the designs of Jobs and Ive. It is about Apple’s relationship with its own products. It is about how things are built and – you might have guessed from the title – where.

Apple’s first crucial shift in strategy was to give up trying to make products itself. When Apple sold its factory, it decided to license the making of its products to other companies (so-called ‘contract manufacturers’). One of the revelations of McGee’s book is that Apple’s relationship with these companies was far deeper and more entwined than most would think. As Apple built this network, the company began ‘exerting such a degree of control that the term outsourcing would become misleading if not wholly incorrect’. Apple had its engineers sleeping in the factories of suppliers and drove them towards new technologies.

Apple didn’t simply turn to existing supply networks; it forged its own, often by bringing together companies in new chains of cooperation. McGee explains how, in the creation of one iMac model, ‘Taiwan’s esteemed bicycle manufacturing industry helped with the chrome neck, while metal stamping was done in Japan’. Apple’s engineers ‘found precision machining capabilities at hard-drive makers in Thailand and even visited a turbine blade fabrication facility ran by Singapore Airlines’.

Companies like Foxconn, one of Apple’s suppliers, worked for almost no profit for the deep education that collaborating with Apple would provide. This contributed to the ‘Apple squeeze’, a phenomenon encapsulated in a single, totally mad statistic: the iPhone accounts for fewer than 20 per cent of smartphone sales around the world, yet it captures more than 80 per cent of industry profits.

Initially, Apple’s networks spanned the globe, stretching from Taiwan and Korea to Germany and Mexico. But then came the second big shift. As the iPod launched, Apple needed to manufacture at vast scale. More than anywhere else, China was determined and able to create the conditions to lure electronics manufacturing to it. Local officials cleared all manner of hurdles to build new factories that could do exactly what Apple needed: work at scale and to the required standard. Tens of millions of migrant labourers moved into specially designated export zones.

The scale of Apple’s investment in Chinese manufacturing is really beyond imagining. The entire value of the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe out of the ashes of the Second World War amounted to the equivalent of $131 billion today. In 2016, Cook signed an extraordinary agreement to invest $275 billion in China over the following five years alone. Apple was causing China to transform itself from a land of cheap and flexible labour into one of sophisticated automation and networks of specialist suppliers.

Apple in China is one of a growing number of books focusing on the hardware side of the tech revolution, joining works like Chip War by Chris Miller and The Thinking Machine by Stephen Witt. This is a book about supply chains and manufacturing, so don’t expect car chases. Nevertheless, McGee has a knack for drawing out the human side of the story and homing in on the details. One hotel that Apple engineers frequented in the South Korean city of Gumi was a ‘pigsty’ with a whole floor that served as a brothel and sheets ‘so over-starched they were like sheet metal’. ‘The effect was so smooth,’ McGee says of the iMac G4, ‘it was like the computer was ready to breakdance.’ He also writes about the interplay of materials and psychology. The stainless steel used on the original iPod smudged when touched – deliberately, it turns out, because it forced the user to polish the unit, something Jony Ive thought would help nurture a connection between product and user.

But mostly, this is a book about geopolitics. Apple sleepwalked into a new reality. The world’s largest company, a flagbearer of global capitalism, landed in the grip of the Chinese Communist Party. China became the only place in the world where hundreds of millions of iPhones could be manufactured. As Apple doubled down on its operations in China, Xi Jinping was ‘ramping up repression at home and taking a more combative stance in international affairs’. In 2016, the Chinese government tried to force Apple to remove the New York Times app from the global app store. In 2022, protests against China’s Covid-19 policies erupted in Zhengzhou, one of the cities where the iPhone is manufactured. As the demonstrations were suppressed, Cook could not even bring himself to defend the Chinese people’s right to protest.

This book is totemic and important, and hits the shelves just as the United States and China teeter on the brink of a trade war. Nothing joins the American and Chinese economies so profoundly as Apple. It may well be that Cook and Apple steer the world through these troubled waters. Or it might be that Apple is sunk by them. We all know that manufacturing, logistics and supply chains are important. McGee has managed to make them thrilling as well.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk

As Apple has grown, one country above all has proved able to supply the skills and capacity it needs: China.

What compromises has Apple made in its pivot east? @carljackmiller investigates.

Carl Miller - Return of the Mac

Carl Miller: Return of the Mac - Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company by Patrick McGee

literaryreview.co.uk